On 1st of March 1941, Bulgaria officially became a military ally of Germany and the countries of the Axis in the Second World War. Total German domination was imposed in allied or occupied countries. In arts and culture, the official line was set by Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda. A representative of Gestapo was monitoring the exact execution of the assigned tasks. In our country that was Adolf Heinz Beckerle[1].

Specialized print publications for cinema as well as all film production were governed by the newly established foundation „Bulgarsko Delo“ which would follow for the ideologically correct line of information during the war.

Just as it commenced, Bulgarian cinematography would have to endure another cataclysm of the century. In fact, from a film production point of view, which in periods of war is following the military propaganda goals, the war could even lead to an upswing. A worldwide trend after the beginning of the Second World War was the production of many films with patriotic themes, in Bulgaria it started hard in the early `40s[2]. During 1941 – 1944 Bulgaria and Hungary were allies of Germany and, as part of the German propaganda policy, they produced several co-productions with the aim of improving the quality of Bulgarian filmmaking[3]. These were „Ordeal“ (Dir. Hrissan Tzankov[4]), the unfinished „Iva samodiva“ (Dir. Béla Lévay and Kiril Petrov[5]) and „A Bulgarian-Hungarian Rhapsody“ (Dir. Frigyes Bán and Boris Borozanov[6]).

The film programming in Bulgaria during the war also shifted drastically. German, Italian and Hungarian films replaced the prevailing until then Hollywood and French films on the Bulgarian screen. That is evident from the pages of the specialized press whose content also changed. Cinema related publications limited their product and began to carry out a propaganda function. The most significant – Film (1942 – 1944) and White and Black (1943) will be presented in this text.

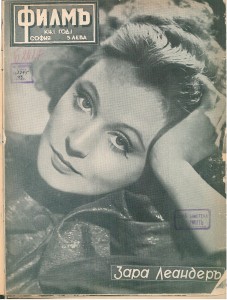

Film (1942 – 1944)

Two months after the suspension of the advertise edition „UFA-Vesti“ (1940 – 1941), its thematic, but much more complete as of publication, „heir“ was released. Editor-in-Chief Georgi Urumov was re-appointed. The program article of Film was titled „Our program“: „Film is going to fill the clear need of a big Bulgarian magazine for comprehensive film culture.“

The cover of the two-week magazine for cinema and culture was inalterably black and white – with a portrait of an actress or actor. The interior was black and white or monochrome. The print and the quality of the illustrations were high. The design was simple but effective.

It was looking for a balance between photos and text, and it was kept in fair and equivalent ratio until the latest issues when it was broken in favor of the photo material and other types of illustrations. The magazine followed closely the structure set up in the beginning: it started with an outline of a current issue or theoretical-historical article with propaganda purposes, then moved to leading films and actors from the poster, chronicle, fashion, and funny pages with games, crossword puzzles, scores of famous film melodies from popular German movies and other entertainment materials. It ended with the permanent rubric „Mail“ for answers to readers.

Ufa Bulgarian Film AD was the importer of all foreign films distributed in Bulgaria at that time. The company represented Bavaria, Berlin film, Continental, Prague film, Tobis, Terra, Ufa, and Vienna film[7] in Bulgaria. The production of these companies formed a large part of the poster and the content of Film. It is evident by the pages of the magazine that feature films at that time emphasized on militaristic and nationalistic melodramas, military-historical heroic epics, and entertaining escapist[8] comedies.

In addition to the German films, the editorial board of Film also provided space for the cinematography of France, Spain, Italy, Hungary, and Japan. In response to readers’ questions, the magazine gave us a clear idea of the nature of the wartime poster: „American movies are not played now in the countries of the Axis and the Tripartite Pact[9].“ War harmed the cinemagoers, they loved cinema and its various manifestations of all nationalities, but war imposed unavoidable constraints: „American movies are not played now, and we have no interest in any American movies or actors.“[10]

In spite of the abrupt answers, the magazine built up a circle of regular readers who corresponded with it from across the country, including the newly joined territories. Through them, Film received letters from Skopje, Bitola, Štip, Pirot, Prilep, Kavala, Xanthi, and others.

Separately, Film was also publishing propaganda materials. They pronounced the leading role of the National Propaganda Directorate in cinema: „With the establishment of the National Propaganda Directorate in Bulgaria, a film department was set up. That turned to a certain number of film reviews, that, like the foreign ones, covered the most important events in the country, and will, therefore, remain important documents for the political and cultural life in Bulgaria.“[11]

An essential part of this directorate was the foundation „Bulgarsko Delo“ (established on March 31, 1941). The wide coverage of its activities was the only focus on Bulgarian cinema. The content of the weekly reviews of „Bulgarsko Delo“ – a major production department of its business – was comprehensively described. An extensive summary rapturously noted review number 100.

Foundation’s program provided for activity expansion and creation of robust national filmmaking through the production of more feature films. In early 1943, were published a number of articles with recommendations for Bulgarian quality film.

The activity of the foundation also envisioned the construction of film studio: „We need studios for shooting and technical production of films. Therefore, „Bulgarsko Delo“ is preparing the conditions for building film studios in which we can do even big movies… We have already chosen a site for the construction of film studios. It is on the Boyana Road. The construction will start in the spring if conditions are favorable.”[12]

But history, again, interfered with the spectacular plans. In August 1943, Tsar Boris III died. The coverage of his burial was extensive in issue 10 (September 16-30, 1943).

The first issue of the Film magazine of 15 July 1942 programmed its release in the middle and the beginning of the month every fifteen days. This periodicity, with few exceptions, was not disturbed almost until the end. „Several semimonthlies have been missed due to technical difficulties.“[13] Structurally the journal followed its initial logic as well and very rarely relinquished it. For its sixteen pages, the journal was rather multifarious. On one side, it served as propaganda for the official policy and advertising of German films of Ufa AD. Although there was no blatant fascist or Nazi symbolism in its layout, a fact that also applied to the other wartime publications in Bulgaria, the emblems of the regime were visible in the uniforms some artists posed with for photos of that time. Still, the propaganda was most noticeable in the texts. At the same time, Film had plenty of materials rich with information and of historical value.

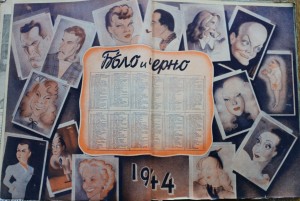

White and Black (1943)

The cover of this two-week magazine for cinema and culture was a black and white photo of popular Italian actress, over it stands the masthead, on a colored background, different for each issue. Inside White and Black, the text and the photos were almost equal in volume, but because of unbalanced distribution, there was an impression that illustrative material faded into the enormous articles. In other cases, the photos were used indiscriminately for short reports.

There were different materials on various cultural themes in the magazine. Serious art studies besides lighter columns and fun topics. Historical studies were present also. The synergy between cinema and other arts – literature, fine arts, music, theater – as well as the individual professions of cinema, which traditionally got less often the attention of the press such as scenography, makeup, cinematography – was of particular importance. It was in these articles that the language was high, intelligent, particularly when the pathos of wartime nationalism and the government’s political line were not there.

Although for objective reasons, the assessment is always positive, there was a genuine film criticism in these writings. The authors of White and Black unraveled the film language and explained the creative messages of the films. The size of the publication was impressive – 22 -32 pages at a price of 5 -10 leva. Most of the materials were signed, including the translations – with an author, source or translator. In that respect, the photos were a weak link, which, in addition to the fact that they often did not correspond to the text, were with unclear origins. Typography was also miscellaneous – different fonts of titles, rubrics and entire texts without good reason.

White and Black was focused mostly on Italian culture – mainly cinema, but also literature, art, music, theater. The magazine was a publishing analog of Film [1942-1944], but leading geopolitical discourse was the Italian cinema. After the cinema, the literature was the most widely covered subject. Stories and poetry of contemporary Italian authors were presented, as well as biographical references for them. Translations were often done by Nikolay Donchev, who certainly knew the Italian culture closely and probably that made him suitable for the position editor-in-chief of the magazine.

Bulgarian cinema also had its proper place in White and Black. Incessantly a big article on various topics was on the third page. That page was for commentaries on the state of Bulgarian cinematography, guidelines, and recommendations for its development. The activity of the foundation „Bulgarsko Delo“ was well represented. „A serious and solid basis and a prerequisite for meaningful and national Bulgarian film work were put through the film company“ Bulgarsko Delo“… Given the powerful impact of cinema, the high educational value of cultural films [documentaries], „Bulgarsko Delo“ has embraced the idea of increasing the production of cultural films… The moral and material support of the state in Bulgarian national film production is multifaceted and significant. With this, the Bulgarian state makes a significant contribution to the development of our film work.“[14] It is clear from the last two sentences that the state, through the „Bulgarsko Delo“ foundation, has already supported film production.

In its first issue, the magazine reported on the upcoming movie „The Wedding“ (1943, Dir. Boris Borosanov[15]). Boris Borosanov’s directorial work, the technical qualities of the filming (cinematographer Boncho Karastoyanov) and the editing, as well as the acting of Asen Kamburov, Stefan Pejchev, and Manya Bizheva, were highly appreciated. The text also presented a complete definition of a national film: „First of all, the film was made entirely with ours, Bulgarian resources – technical and other… As should be expected from an attempt for a national film, „The Wedding“ is built around indigenous issues with an entanglement of flashes of our wars. Wars in which our nation found its true essence by showing those virtues that were the genesis of our tribe, and through which our nation could have established its own country, to strengthen her internally and externally and to turn her to be the first power in the Balkans.“[16] The use of nationalist rhetoric was prevalent.

Totalitarian regimes traditionally recognized cinema as the most appropriate mean of mass propaganda. During the Second World War, it fulfilled that role to the full extent. The military allies of Bulgaria – Germany, and Italy – were flooding the market with their production – so-called national films with a patriotic and historical focus. Specialized cinema publications were also part of this cultural and political phenomenon. White and Black followed closely that line accentuating on Italian cinema and culture. They were a leading topic on its numerous for that time pages. The publication was ambitious, but it lasted only a few months (March 15 – December 25, 1943). The last issue wished its readers Happy New Year 1944 and disappeared from the market.

[1] Staykov, Alexander, Interview, June 2016. Personal archive.

[2] Yanakiev, Alexander, Cinema.bg, Sofia. TITRA, 2003, p. 170.

[3] Forgač, Ivan, “Bulgarian-Hungarian co-productions in the 1940-1944 period”. “Cinema and Time”, issue 2 (29), Sofia. BNFA, 2007, pp. 59 – 71.

[4] Alkalom (1942) IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0327973/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 – 19.01.2016

[5] A tenger boszorkanya (1943) IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0422505/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 – 19.01.2016

[6] Tengerparti randevu (1944) IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0338827/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 – 19.01.2016

[7] Film, year I, № 6, 15-30.09.1942. p. 4

[8] escapist – avoiding unpleasant, boring, severe, terrible or banal aspects of everyday life.

[9] Film, year II, № 3, 01-15.06.1943. p. 15

[10] Film, year I, № 9, 01-15.11.1942. p. 15

[11] Stanislavov, Iv. “Films as a historical document”, Film, year II, № 10, 16-30.09.1943. p. 2

[12] L. B., “Building of Bulgarian film studios is forthcoming”, Film, year I, № 13, 01-15.02.1943. p. 10

[13] Film, year II, № 3, 01-15.06.1943. p. 15

[14] “Bulgarian film work”, White and Black, № 1, 15.03.1943. p. 3

[15] Svatba: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0328496/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 – 22. 04. 2016

[16] Ibid.